Assignment: (Understand only)

-

Understand the basic form and functioning of the Floppy Drive

The 5.25-inch disks were dubbed "floppy" because the diskette packaging was a very flexible plastic envelope, unlike the rigid case used to hold today's 3.5-inch diskettes.

By the mid-1980s, the improved designs of the read/write heads, along with improvements in the magnetic recording media, led to the less-flexible, 3.5-inch, 1.44-megabyte (MB) capacity FDD in use today. For a few years, computers had both FDD sizes (3.5-inch and 5.25-inch). But by the mid-1990s, the 5.25-inch version had fallen out of popularity, partly because the diskette's recording surface could easily become contaminated by fingerprints through the open access area.

A floppy disk is a lot like a cassette tape:

- Both use a thin plastic base material coated with iron oxide. This oxide is a ferromagnetic material, meaning that if you expose it to a magnetic field it is permanently magnetized by the field.

- Both can record information instantly.

- Both can be erased and reused many times.

- Both are very inexpensive and easy to use.

If you have ever used an audio cassette, you know that it has one big disadvantage -- it is a sequential device. The tape has a beginning and an end, and to move the tape to another song later in the sequence of songs on the tape you have to use the fast forward and rewind buttons to find the start of the song, since the tape heads are stationary. For a long audio cassette tape it can take a minute or two to rewind the whole tape, making it hard to find a song in the middle of the tape.

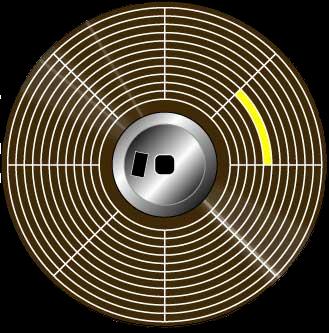

A floppy disk, like a cassette tape, is made from a thin piece of plastic coated with a magnetic material on both sides. However, it is shaped like a disk rather than a long thin ribbon. The tracks are arranged in concentric rings so that the software can jump from "file 1" to "file 19" without having to fast forward through files 2-18. The diskette spins like a record and the heads move to the correct track, providing what is known as direct access storage.

In the illustration above, you can see how the disk is divided into tracks (brown) and sectors (yellow).

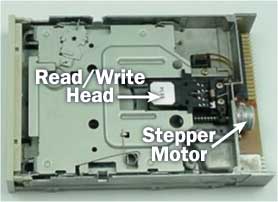

The major parts of a FDD include:

- Read/Write Heads: Located on both sides of a diskette, they

move together on the same assembly. The heads are not directly opposite

each other in an effort to prevent interaction between write operations on

each of the two media surfaces. The same head is used for reading and

writing, while a second, wider head is used for erasing a track just prior

to it being written. This allows the data to be written on a wider "clean

slate," without interfering with the analog data on an adjacent track.

- Drive Motor: A very small spindle motor engages the metal hub

at the center of the diskette, spinning it at either 300 or 360 rotations

per minute (RPM).

- Stepper Motor: This motor makes a precise number of stepped

revolutions to move the read/write head assembly to the proper track

position. The read/write head assembly is fastened to the stepper motor

shaft.

- Mechanical Frame: A system of levers that opens the little

protective window on the diskette to allow the read/write heads to touch

the dual-sided diskette media. An external button allows the diskette to

be ejected, at which point the spring-loaded protective window on the

diskette closes.

- Circuit Board: Contains all of the electronics to handle the data read from or written to the diskette. It also controls the stepper-motor control circuits used to move the read/write heads to each track, as well as the movement of the read/write heads toward the diskette surface.

The read/write heads do not touch the diskette media when the heads are traveling between tracks. Electronic optics check for the presence of an opening in the lower corner of a 3.5-inch diskette (or a notch in the side of a 5.25-inch diskette) to see if the user wants to prevent data from being written on it.

Click the Picture to see video

The following is an overview of how a floppy disk drive writes data to a floppy disk. Reading data is very similar. Here's what happens:

- The computer program passes an instruction to the computer

hardware to write a data file on a floppy disk, which is very similar to a

single platter in a hard disk drive except that it is spinning much

slower, with far less capacity and slower access time.

- The computer hardware and the floppy-disk-drive controller start the

motor in the diskette drive to spin the floppy disk.

The disk has many concentric tracks on each side. Each track is divided into smaller segments called sectors, like slices of a pie.

- A second motor, called a stepper motor, rotates a worm-gear

shaft (a miniature version of the worm gear in a bench-top vise) in

minute increments that match the spacing between tracks.

The time it takes to get to the correct track is called "access time." This stepping action (partial revolutions) of the stepper motor moves the read/write heads like the jaws of a bench-top vise. The floppy-disk-drive electronics know how may steps the motor has to turn to move the read/write heads to the correct track.

- The read/write heads stop at the track. The read head checks

the prewritten address on the formatted diskette to be sure it is

using the correct side of the diskette and is at the proper track. This

operation is very similar to the way a record player automatically goes to

a certain groove on a vinyl record.

- Before the data from the program is written to the diskette, an

erase coil (on the same read/write head assembly) is energized to

"clear" a wide, "clean slate" sector prior to writing the sector data with

the write head. The erased sector is wider than the written sector -- this

way, no signals from sectors in adjacent tracks will interfere with the

sector in the track being written.

- The energized write head puts data on the diskette by

magnetizing minute, iron, bar-magnet particles embedded in the diskette

surface, very similar to the technology used in the mag stripe on the back

of a credit card. The magnetized particles have their north and south

poles oriented in such a way that their pattern may be detected and read

on a subsequent read operation.

- The diskette stops spinning. The floppy disk drive waits for the next command.

On a typical floppy disk drive, the small indicator light stays on during all of the above operations.